Philodendron Growth Habits Complete Guide: 3 Types Explained with Care

87% of philodendron lovers have trouble pinning down the pattern of growth of their plants — but that even simple difference affects whether your plant thrives or just survives. Seeing these three growth habits makes obscure recommendations for care more clear-cut next steps.

One of nature’s most intriguing evolutionary adaptations is philodendron growth habits, which allow these tropical plants to develop three distinct strategies for survival and reproduction. Each form of growth — climbing, crawling, self-heading — represents millions of years of evolution as plants learned to thrive under certain environmental challenges in the natural habitats they inhabit, the rainforest.

Knowledge is power because it can be the key to realize the full potential of your plant without making the kinds of errors that result in stunted growth, unhealthful growth, or failure in the first place.

The Three Top Philodendron Growth Habits

Philodendron Climbers: Vertical Ascension Titans

Climbing Philodendrons are the biggest and most varied class of the genus, and account for around 60% of the species. These plants possess adapted aerial roots that are akin to biological grappling hooks, enabling them to scale trees and high objects and other vertical surfaces to search for light-sensitive areas.

Climbing mechanisms use a complex mixture of mechanical and chemical adaptations. The aerial roots grow from nodes on the stem, starting out as little brown nubs. These roots contain specialized cells referred to as velamen — thick layers of tissue that expand drastically when exposed to high humidity, increasing surface area by as much as 300 percent. This expansion results in microscopic deviations which combine with the surface texture for mechanical binding and a first hold.

After contact, climbing philodendrons initiate their second mechanism, chemical adhesion. Root tips release a complex mixture of polysaccharides and glycoproteins that harden into a cement-like stuff within hours of air exposure. This bond can hold up plants with the weight of up to 50 pounds and form permanent connection areas that last beyond the death of the root tissue.

Popular climbing species are heart-leaf philodendron (Philodendron hederaceum) that grows 6-12 inches per month, if left under ideal conditions, and pink princess, which has strong, variegated leaves. These plants usually grow 300-500 per cent bigger when offered vertical support than when left to trail horizontally.

Ground-Living Specialists: Crawling Philodendrons

Crawling philodendrons — which also popularly call themselves creeping philodendrons — have ceased to grow upward and have now moved horizontally across the earth’s forest floor, instead. This approach enables them to successfully invade large areas of forest while remaining close to the nutrient-guzzling leaf litter and organic material that gathers in the rainforest floor.

The crawling behavior appears in long internodes –stems between leaves — which can reach 8-12 inches in some species. The plant has elongated regions in each part of the plant to extend from point to location of the plant and to reduce its energy intensity. At this node, individual adventitious roots are created, which anchor the stems to the substrate and take up moisture and nutrients supplied from decomposed organic substances.

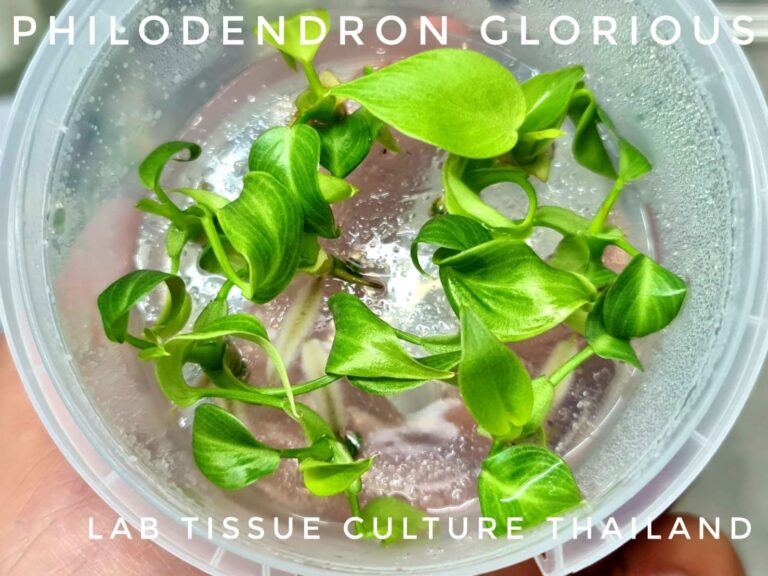

Figures like Philodendron gloriosum, which reproduce in this way, also have huge heart-shaped leaves as large as 24 inches wide when developed. The crawling behaviour of this plant puts into question what special care is needed for it: If a planting plant likes to grow horizontally it must make use of rectangular planters, and its growing tip needs to be frequently re-potted to prevent the plant from getting buried by other plants, resulting in stem rot.

The crawling philodendron have a usually between 4 and 8 inches of growth per month, which varies tremendously depending on the species and the habitat. Crawling philodendrons, in contrast, hardly grow large aerial root systems or even aerial root structures like climbing philodendrons.

The Self-Heading Philodendrons: High-Minded and Upright

The self-heading philodendrons are high-minded and upright looking, building a compact habit that requires comparatively minimal external support. These plants have matured to have longer, more rigid stems for massive quantities of leaf weight which they can bear independently, and the growth mechanisms that yield dense, bushy forms.

This self-heading morphology is found primarily by two basic mechanisms: the shortening of internodes and the basal branching. Unlike climbing and crawling philodendrons, self-heading philodendrons exhibit internodes that are only 0.5 to 2 inches long and form tight clusters of leaves around a central stem. At the same time, these plants have so many growing areas beginning at base that they are growing fuller without pruning and without training.

Selloum philodendron (now Thaumatophyllum bipinnatifidum) species may have a trunk that is the size diameter of upwards of 4 inches and a height of over 6 feet. The bird’s nest philodendron (Philodendron bipennifolium) leaves have a spiral shape and form a rosette arrangement which enhances light absorption and makes the plant structurally sound.

This leaves may grow through a few rounds each year, with self-heading varieties producing 6-10 new leaves per year and each leaf growing to full size after 4-6 weeks. There is little or no assistance from supports, and when there is a rotation it helps to achieve even light distribution and not create leaning plants.

Hemiepiphytic Adaptations: The Pros and Cons

Philodendrons typically live a hemiepiphytic life cycle, mixing terrestrial and epiphytic phases of growth to enhance survival. This intricate approach is not only juvenile-adult, where different environments must be taken into account but also includes two separate development phases which can be adapted to different conditions.

First-generation hemiepiphytes are initiated high in the trees’ canopy and young grow in the forest canopy which are the organic by-products of plant development from an organic matter source. Such seedlings first mature as genuine epiphytes in which they receive nutrients from decaying vegetation and atmospheric moisture. As they reach maturity they develop specialized aerial roots that emerge downward toward the forest floor, making contact to soil in the process. Such a conversion provides more steady moisture and nutrient availability to cope with the larger leaf sizes typical of mature specimens.

Secondary hemiepiphytes behave in the opposite way: They begin life as forest floor roots, with their shoots climbing up toward the light at hand. As the aerial stems develop and find appropriate supportive structures to host themselves, they eventually give up their root systems, going full-on epiphytic. This helps plants move when there are low ground conditions of flooding, competition and light variation.

Biochemical adaptations, supporting hemiepiphytic lifestyle, are specialized enzymes that enable rapid switch between modes for nutrient absorption. Epiphytes in the plants also produce phosphatase enzymes that degrade organic phosphorus compounds, and these terrestrial phases stimulate nitrate reductase activity for soil based nitrogen source processing.

Aerial Root Function: More than Just Support

One of the most complex morphologies of philodendron is aerial roots, which have evolved as aerial roots have multiple purposes beyond climbing. These plant-specific structures are highly plastic, and alter shapes and functions depending on the environment and the plant’s specific requirement.

Velamen tissue expansion due to humidity is the main attachment mechanism. Under heavy, humid conditions velamen cells absorb moisture from the atmosphere, then swell into tiny suction cups that cling to harsh surfaces. This happens within minutes of touch, with adhesion intensity improving within 24-48 hours as more cells grow and wrap around surface distortions.

Under some conditions, the nutrient absorption capacity of aerial roots is very high relative to subterranean roots. Studies have shown that aerial roots can absorb up to 40% more nitrogen from the atmosphere than soil roots, often because atmospheric nitrogen compounds dissolve into films from surface moisture. It helps philodendrons to enhance nutrition in rainy seasons when soil nutrients compete more fiercely.

Aerial roots have internal air spaces to exchange gas, avoiding anaerobic conditions that may harm root tissue. These aerenchyma channels link to stem tissue forming an internal circulation system that transfers oxygen from aerial parts to roots that must struggle with low oxygen levels.

Variations in Growth Rate by Characteristics of Different Species

The growth rate among philodendron species is highly heterogeneous depending on genetic programming, natural environment and growth habits. Learning these differences helps developers choose species suitable for their geographical space limitations and projected timeline.

Fastest climbing species include Philodendron micans which can grow 12-18 inches per month under ideal conditions, while the golden goddess variety can grow 8-14 inches per month. These explosive growth rates demonstrate evolutionary adaptations to rapidly scale up to levels of forest canopy for increased light-competition.

Medium-growth species include a range of houseplants including heart-leaf philodendron (6-10 inches monthly) and the Brasil variety (4-8 inches monthly). These rates balance expedited establishment with sustainable biomass throughput, consistent with adaptations to moderate understory conditions.

Slow-growing varieties often have unique characters or huge leaf sizes, sufficient to warrant a slow cultivation speed. In monthly production Philodendron gloriosum is usually 2-4 inches tall, but by mature, leaves are larger than 20 inches in diameter. The white knight variety grows only 1-3 inches, a minuscule proportion, every month but produces beautiful variegated foliage coveted by collectors.

The environmental effects have profound effects on growth rates of every species. Temperature ranges (75-85°F) allow to fuel cellular respiration whereas humidity over the condition of 60% will prevent water stress and facilitate maximal cell growth. The lighting quality has a direct effect on the photosynthetic capacity; light directly promotes growth 200-300 percent faster than in low-light conditions with strong indirect light.

Leaf Transformations: Juvenile to Mature

The metamorphosis from juvenile to adult leaf forms is one of the key pleasures of philodendron cultivation, but, of course, understanding what the hormonal and environmental factors are that promote morphological changes is critical.

Juvenile leaves are characterized by simpler morphology, and have small lobing or fenestration, this is because in early growth stages, it is preferred to maximize light capture to obtain an increased photosynthetic surface area. The leaves tend to have thinner cuticles but with less structural supporting tissue, indicating as temporary energy producing plants, not as final features of building material.

Upon reaching certain size or hormonal thresholds, a change in leaf shape, or growth at a stable developmental maturity level of plants activates a genetic program that activates multiple developmental processes. More mature leaves grow in a higher structural complexity by increasing the amount of lobing, leading to higher water drainage and less resistance to wind, fenestration, which increases light penetration and therefore lower leaves and create increased surface areas for photosynthesis.

The size increase in leaves may be over 1000% in some species. Philodendron bipinnatifidum juvenile leaves mature at 4–6 inches, and adult leaves grow more than 36 inches and have margins deeply incised. This rapid growth needs an optimal ideal of 18-24 months and increases drastically when the roots become more robust and vertical climbing initiates.

Environmental conditions that drive leaf transformation are enhanced light intensity, which triggers the production of growth hormones such as auxin and gibberellin, which are used in regulating cell expansion. Vertical orientation is also a factor: climbing plants also have larger leaves than horizontal members do when using the same environment.

Careful Approaches for Growth Habitat

Philodendron Care When You’re Climbing

Climbing philodendron cultivation, successful climbing can only occur with the support structure suitable for aerial root attachments, while maintaining perfect growth conditions.

Moss poles are the gold standard for supporting climbing varieties, providing many benefits compared to alternate materials. Living moss poles are composed of sphagnum moss surrounding rigid cores which provide humid microenvironments conducive to the growth of aerial roots. The moss retains moisture 80-90% over ambient conditions, promoting quick root growth and attachment. The best moss poles should measure 1.5-2 inches in diameter and be at least 6 inches above the current plant height in order to allow them to grow next year as well.

Attachment has an important importance to the success rates. Natural jute twine offers some support without injuring stems, and plastic plant ties offer greater tolerance for heavier pieces. Avoid making any link with metal wires or tight binder that will limit the stem development or establish a platform for pathogens. Base attachment shall take place 2-3 inches below the active nodes where some aerial roots will be able to make contact with support surfaces.

Humidity management is essential for climbing varieties, since the aerial roots grow well and quickly under humid conditions, as roots in the air can develop more rapidly under this condition. The use of grouping plants together can help build favorable microclimates while humidity trays or room humidifiers ensure over 60% humidity levels. In this respect, misting provides short-term moisture boost, which is of course temporary, but moisture must be consistently applied to keep it up and maintain benefits.

Crawling Philodendron Care

To cater to crawling philodendrons and to avoid the usual problems with stem burial and root suffocation, specialized care approaches that accommodate their horizontal growth patterns are essential.

The selection of container plays an important role in long-term success and rectangular planters offer much more advantages than round pots. The rectangular container provides natural spreading while preserving order of root zones in the root zone. Planters that measure 8-12 inches wide by 24-36 inches long are perfect for most crawling species and can hold them for 2-3 years until the planter needs to be separated or reused. Shallow depth (4-6 inches) reduces moisture holding capacity to some extent, while still giving the roots plenty of space at right height for their development.

The composition of the soil requires a delicate balance between holding moisture and draining appropriately. That is the mixture of 40% peat moss, 30% orchid bark, 20% perlite and 10% horticultural charcoal, which are optimal for the majority of crawling species. The combination creates moisture without waterlogging, and contains useful microorganisms in the soil in the best way possible for proper root growth.

Repotting frequency is increased in philodendron type and the need for repair is normally every 12-18 months. Important signs would probably be the growth tips around the edges of the containers, the appearance of aerial roots at a number of nodes, or the formation of stems underneath soil. Late-winter or early spring recovery repotting aligns with natural growth cycles and reduces transplant trauma.

Self-Heading Philodendron Care

Versions that self-head, receive support from care methods that focus on both preservation and slow growth, rather than rapid expansion. These plants developed for moderate steady growth rates yielding dense, attractive specimens that last a long time.

Container size should not be reduced to depth, self-heading philodendrons have extensive horizontal root systems. In general, the dimensions of pots are 12-16 inches with 8-10 inch depth and the room is great for 3-5 years of growth in most species. The advantages of Terra cotta materials come with improved gas exchange and regulation of moisture, but plastic containers need to be watered less often.

There are also some differences in the methods of fertilization from climbing or crawling variants. The slow-release ingredients are used quarter-strength monthly during growing months, allowing for a steady distribution not to overstimulate growth that could jeopardize the structural integrity. Other types of organic options like fish emulsion or seaweed extracts offer micronutrients that synthetic fertilizers usually do not produce.

While the light requirements vary among self-heading species, they are generally much more flexible than other growth habits. Generally accepted medium light conditions that allow growth, though variegated varieties are sometimes preferred for illumination, as they will retain their color patterns when they are allowed into brighter conditions. Rotation every 2-3 weeks prevents inclination on symmetry growth.

Common Mistakes and Troubleshooting

Most of the growing problems in philodendron can be prevented through understanding typical cultivation errors. This is largely due to using ill-advised care strategies derived from misapplying growth habit instructions.

Overwatering is the most common error with the vast majority of all growth habits where we regard climbing types as a terrestrial plant. Climbing philodendrons prefer to survive under slightly drier than crawling ones because they have aerial root systems for intermittent water. Allow the soil to dry by 1-2 inches in depth prior watering climbing varieties while being kept perpetually moist (not wet) for crawling species.

Poor support of climbing varieties decreases growth and leaves. Left to roam on their own horizontally, the plants use excess energy to elongate stems to leave less of their leaves for the trees and are instead sparsenessed, unpleasant specimens. And when plants grow 6-8 inches tall, with support structures, this developmental redirection is avoided.

Wrong lighting causes various problems according to growth habit. In climbing varieties illuminated by direct sunlight, the leaves scorch in brown patches, while lack of light decreases the amount of aerial roots produced. Crawling philodendrons are in a lower light tolerance zone, but prefer conditions that are even brighter. Self-heading types have the highest tolerance but grow pale, stretched under insufficient illumination.

Variants in temperature cause a different effect by habitat preference to different species. The most philodendrons begin in stable tropical habitats, but react inadequately to temps lower than 65°F, or if the temps spike above 10°F, so plants can gradually adapt over a period of 7-10 days to adjust to changing environmental situations without having a strong response to stress.

Proper Philodendron Propagation

Proper philodendron propagation begins with identifying the growth habits that are correlated to reproductive success. Because of this, timing and the environment determine the success rate for all the patterns of a certain type as follows.

The climbing varieties that propagate best are stem cuttings that consist of 2-3 nodes and at least one leaf. Choose healthy, growing stems, cut just below the location of the budding aerial roots. Rooting takes place in water or damp sphagnum moss within 2 to 4 weeks at temperatures greater than 75°F at which successful rooting should increase from 60% to over 90%.

Crawling varieties divide more than cuttings, as their growth is horizontal, resulting in many growing points connected by stem sections. When repotting, division is used to separate established sections and keep root connections. All divisions should have 3-5 leaves and established root networks for best establishment.

Self-heading varieties pose the most significant challenges in propagation, being characterized by low density growth and short stem length. Tissue culture methods are the most reliable method of obtaining the multiple specimens, although seasoned growers can obtain enough to accomplish the same task efficiently by dividing established plants carefully when growing with vigour.

Air layering is an advanced method, as to its suitability, which is highly desirable for all growth behaviors, and very good for hybridization for the propagation of rare or slow-growing strains. Foraging with the axial attachment is done by wounding stems and promoting root growth while the limbs are attached to the parent plant, providing a source of energy and water during the form of roots which remains attached to the root.

Conclusion

In the first of these, philodendron growth habit discovery moves plant care from unpredictable trial and error to scientifically proven science. Whether feeding climbing plants atop a moss pole; supporting a crawling variety across a square planter; or maintaining the architectural beauty of self-heading plants, success relies on identifying and responding to the evolutionary adaptations of each plant.

The rewards — lush foliage, incredible changes in morphology from juvenile to maturation, and the incredible satisfaction of being able to watch the plants attain their full potential are worth the investment in the specialized knowledge required by each.

Key Sources:

What’s the Difference Between Crawling and Climbing Philodendron | Planet Houseplant

Philodendron Types | Business Insider

Hemiepiphytic Growth Strategies | ScienceDirect

Aerial Roots in Philodendron Care | Iowa State University Extension